Kings Africa Rifles

- Jan 1, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Feb 11, 2025

A recent and unrelated trip to Uganda gave me a chance to investigate how locals – specifically soldiers of the King’s Africa Rifles are remembered for their role in the East Africa campaign.

There were about 4200 deaths during the war, with a further 3 000 due to disease. It is unknown how many of these deaths are Ugandans, but it is fair to assume that they are many and I was looking for any sign that these men’s deaths had not gone unnoticed.

Sadly, there were no signs.

Ugandan soldiers formed the 4th Regiment of the King’s African Rifles at the start of WW1. The KAR comprised three in 1914: The 1st KAR were recruited and based in the Nyasaland colony (now Malawi), the 3rd KAR were aligned with British East Africa (many from Kenya), and the 4th KAR was composed of Ugandan troops and based there. The KAR soldiers were locally recruited and led by white officers.

KAR soldiers, also known as askari, from the Kiswahili name for guard, were not initially well regarded by officers of the British Empire and so didn’t take part in the early battle for German East Africa or at the disastrous Battle of Tanga in late 1914 and early 1915. A therefore weakened British position led to the deployment of the KAR to defend the strategically important Ugandan Railway. Early requests to expand the KAR were initially refused, despite them seeing action away from the main theatre of the German East Africa campaign, during 1915 at the Battle of Mbuyuni where Germans were driven back, and at the Battle of Longido West which saw German raids aimed at the Uganda Railway thwarted.

The arrival of General Jan Smuts and his African soldiers at the start of 1916 saw a change in attitude: Smut’s plan required a drive southwards into German East Africa and KAR played their role: The 3rd KAR suffered heavy casualties at the Battle of Latema Nek, including the death of the commander, while the 4th KAR advanced to Mwanza and towards Tabora in July and the 1st KAR was part of the force that met the enemy column in May.

Ill health of some 12 000 soldiers and the recall of General Smuts to serve in the Imperial War Cabinet meant the need for replacement troops and this finally meant the expansion of the KAR – by February 1917 it had expanded from six battalions (two had been re-raised by Smuts) to twenty. This expanded force also included a new regiment comprising German askari, captured by the British or discharged by the retreating Germans.

The KAR now took on most of the fighting in the East Africa campaign, including at the battles of Narumbombe and Mahiwa and at the start of 1918 the KAR formed the bulk of the forces chasing the Germans southward until their surrender on 25 November.

In the end, though, it was not the KAR which stopped the Schutztruppe, but the Armistice, news of which reached General von Lettow-Vorbeck on 13 November leading to his ultimate surrender on 25 November.

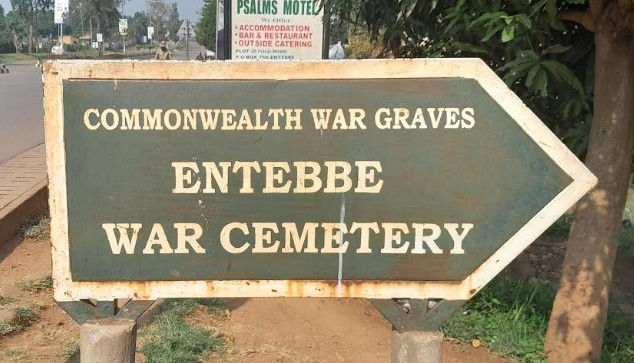

On the Kampala Road from the airport and easily missed by the crowd of road furniture, pedestrians and traffic, the sign is the familiar green and white of the CWG, indicating that at this town cemetery there is at least one grave commemoration personnel who died between 4 August 1914 and 31 August 1921 and 3 September 1939 and 31 December 1947; whilst serving in a Commonwealth military force or specified auxiliary organisation; after they were discharged from a Commonwealth military force or; if their death was caused by their wartime service. For the latter period, they also include commonwealth civilians who died because of enemy action, Allied weapons of war or whilst in an enemy prison camp.

The Entebbe cemetery is unkept and overgrown and I search out the five Commonwealth War Graves in this public cemetery. Brave men all five, but not one is a local Ugandan soldier. Five of European descent, including two from the Navy.

In keeping with the policy at the time, the then Imperial War Graves Commission did not erect individual headstones (for ‘native’ soldiers) but a central memorial selected by the British colonial governments concerned.

Current memorials include the King’s African Rifles War Memorial Tower in Zomba, Malawi, war memorials in each of Malawi’s main cities, and further Askari Memorials in Nairobi, Mombasa and Dar er Salaam. These memorials remember the dead collectively and they are not individually named.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission seems to be taking seriously their role to ‘put right the wrongs of the past’, and Labour MP David Lammy has also spoken out about this ‘oversight’ and highlighted in a moving 2019 article about how the policy of ‘a “every one regardless of their rank or position in civil life shall be treated with equality” wasn’t equally applied away from the Western Front.

KAR soldiers who died in WW2 are remembered in Jinja and Kampala cemeteries in Uganda.

Sources:

Lammy, D. How Britain dishonoured its African first world war dead. The Observer, Sunday 3 November 2019.

Thomas, CG. King’s Africa Rifles. International Encyclopaedia of the First World War, 13 May 2015

The King’s African Rifles and East African Forces Association. The History of the KAR. https://www.kingsafricanriflesassociation.co.uk/. November 2024

Fecitt, H. The Western Front Association. https://www.westernfrontassociation.com/world-war-i-articles/the-king-s-african-rifles-at-kibata-german-east-africa-december-1916-to-january-1917/. November 2024

Comments